back to blog

the Dorset lady who changed the way we see the world

This extraordinary Victorian lady sold seashells by the sea shore – and had a revolutionary impact on our scientific understanding of the world. But Mary Anning had to fight a few dinosaurs on the way…

As well as being stunningly beautiful, Dorset’s Jurassic Coast is today an internationally acclaimed site whose limestone cliffs, rocks and fossils illustrate the history of our planet over the course of 185 million years. Designated as England’s first natural World Heritage Site in 2001, the Jurassic Coast has helped to explain the natural processes that came to shape the Earth as we know it today.

But while the coastline is now world-renowned, less is perhaps known about the Victorian lady who helped to put it on the scientific map. Here we look at the remarkable life of Mary Anning – Dorset’s answer to Charles Darwin.

a family affair

Mary Anning was born in Lyme Regis on 21 May 1799 to a cabinet maker father, who spent his spare time searching for fossils along Dorset’s stunning cliff-sides and would sell his finds, including ammonites (known locally as ‘snake-stones’), belemnites (‘devil’s fingers’) and vertebrae (‘verteberries’), to rich tourists. Fossil-selling became an ongoing business which helped to supplement the family’s income.

Mary lived with her parents and brother Joseph in a house just above the old sea wall in Lyme – where the Lyme Regis museum now stands – and the sea proved to have a defining influence on Mary’s life. Not least because it frequently flooded their seaside home, but more importantly because she inherited her father’s keen interest in fossils, literally following in his footsteps and going fossil-hunting in the Blue Lias cliffs at Lyme and along other parts of the Dorset coastline.

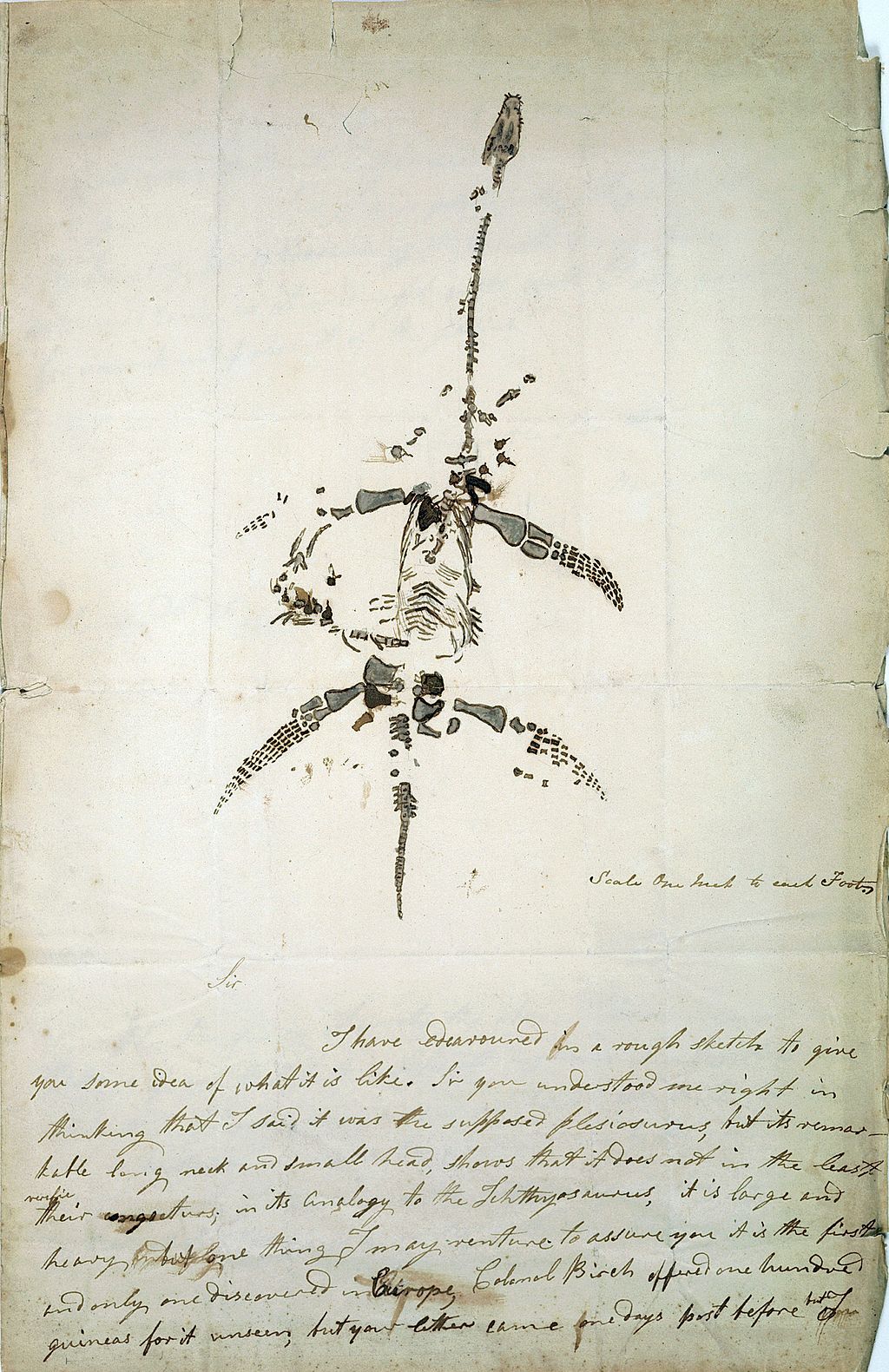

Letter and drawing from Mary Anning announcing the discovery of a fossil animal now known as Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, 26 December 1823.

landslides and lightning

As a poor working-class female, Mary had only limited access to education and had to overcome many other obstacles in life, including the physical dangers posed by frequent landslides. As a child she was actually struck by lightning – though according to the locals this only served to fuel her lively and inquiring mind.

Over time Mary made many important scientific discoveries, including the first complete Ichthyosaur skeleton, and the first British example of the flying reptiles we know as Pterosaurs. In fact, during her lifetime Mary’s work came to have a tremendous impact on the scientific world, leading to significant changes in our understanding of prehistoric life, and challenging the religious perceptions of the time regarding the age and history of our planet.

Cast of “Plesiosaurus” macrocephalus fossil found by Mary Anning, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris. Image credit.

Mary vs the old fossils

Sadly, Mary was to discover that the scientific world was populated with its own enduring set of fossils, and at times she despaired at the attitudes of many of her male 19th-century counterparts, who failed to give her proper credit for her expertise and contribution to scientific discovery. She complained that the gentlemen geologists had ‘sucked her brains, and made a great deal of publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages’. During her lifetime, despite her extensive findings, only two fossils were named after her: Acrodus anningiae and Belenostomus anningiae.

As a woman, Mary was not able to attend university or be admitted to the Geological Society of London. Her work was nevertheless recognised by eminent geologists around the world and many famous names, including lifelong friend and geologist Henry De la Beche, visited her shop – ‘Anning’s Fossil Depot’ – to purchase and discuss fossils.

The famous ‘Duria Antiquior’ watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche depicting life in ancient Dorset based on fossils found by Mary Anning.

After her death in 1847, there was a renewed interest in Mary’s life story and she is even said to have inspired the well-known tongue twister ‘She sells seashells by the seashore’.

In 2010, Mary Anning was acknowledged by the Royal Society as one of ten British women to have most influenced the history of science – finally recognising the game-changing role played by this remarkable Victorian lady fossil-hunter, who changed our understanding of this beautiful part of the world.

Fancy going on your own fossil-hunting adventure? Check out our guide to the best places around the UK to discover a dinosaur…